Full Steam Ahead! The Golden Age Gateway to Florida

April 9, 2024

by Jarrett Hill

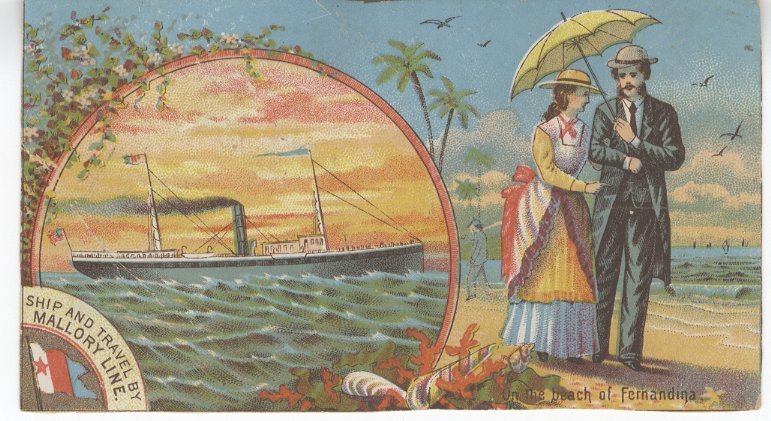

“GO NORTH! By the Iron Palace Steamships of the Mallory Line,” proclaims an 1880 advertisement, “Sailing Directly from Fernandina, Florida Every Thursday Evening for New York!” For residents of Fernandina after the Civil War, steamships became an increasingly-common sight to see in the town’s port. The most prominent company among them, the Mallory Line (which later merged with the Clyde Line to become Clyde-Mallory), promised strength and luxury to passengers on its “iron palaces”. At a time of transformation in Fernandina, the arrival of steamships signaled that the rural barrier island of Amelia had begun its transformation into an accessible and popular destination for vacationers.

Steamships are an early 19th-century innovation that use steam-powered engines to move, as opposed to traditional sail-powered designs. While infamous steamships like the Maple Leaf and USS Ottawa were used for military action in Florida during the Civil War, it wasn’t until after the war that they became popular transportation for civilians. They played a particularly important role in north Florida’s history, as the state began to shift towards tourism as a major economic driver. Early tourism had centered on “health retreats”, based on a belief that the fresh water and air of rural Florida could heal “urban” ailments like tuberculosis. However, as steamships opened the relatively undeveloped interior of the state up to recreation, Florida’s attraction for tourists grew. No longer reliant on wind, steamships allowed for regular movement through inland waterways, particularly the St. Johns River. Settlers along the St. Johns, like the nationally-known author Harriet Beecher Stowe, greeted passing steamships from their waterfront homes—this enthusiasm helped establish Jacksonville and Fernandina as preferred gateways into the rest of the young state. The appeal of steamship travel persuaded national figures to tour the state, like Robert E. Lee in 1870 and Ulysses S. Grant ten years later.

View of the corner of 8th and Beech Street in late-19th century Fernandina, taken from the Egmont Hotel. Built in 1878, the Egmont Hotel was constructed for tourists to Florida’s first resort town, many of whom arrived by steamship.

View of the corner of 8th and Beech Street in late-19th century Fernandina, taken from the Egmont Hotel. Built in 1878, the Egmont Hotel was constructed for tourists to Florida’s first resort town, many of whom arrived by steamship.

Early steamship lines in the waters around Florida initially focused on uniquely-positioned Gulf ports, such as Key West or the Texas island of Galveston, which itself was settled by Amelia Island’s short-lived piratical leader Luis Aury. Just like Aury, though, steamship lines eventually turned their attention to Fernandina. An 1893 investor guide lists the “Advantages of Fernandina” and the reasons why Northern companies should invest in the town. At the top of the list are Fernandina’s natural advantages, stating that “upon the whole Atlantic coast there is not to be found any point in which the port and town are so near the sea and so well-protected.” The possibilities of transport, both human and cargo, supposedly provided Fernandina an “almost illimitable field of profitable enterprise.”

By the end of the century, steamships ran regular voyages to Fernandina, taking advantage of the town’s rail connections to both the major hub of Jacksonville, as well as the rapidly-developing interior of the state. One of the first regular passenger steamship connections to Fernandina was established by the Mallory line in the 1870s, with the SS City of Dallas, and soon both the Mallory and Clyde lines set up biweekly transport between Fernandina and New York City. This regular line helped infuse post-war Fernandina with Northern money, spent by new residents and vacationers. The ease of access to Fernandina combined with the influx of new arrivals following the Civil War—Union veterans returning to Fernandina, as well as former enslaved people—to help spark Fernandina’s Golden Age.

Associations with steamships today are often colored by the most infamous steamship of all—the Titanic. The tragedy of the Titanic brought public awareness to the stark differences in treatment of those on board, with deadly consequences for the poorer classes. While the steamships arriving in Golden Age Fernandina were not as severely stratified, the information we have about the experience of taking a Mallory line ship is in line with the class-based society of Victorian America. A first-class ticket, which included multi-course meals and a private suite, cost $23 at the time—approximately $750 today. In comparison, a steerage-class ticket, which was typically purchased by working-class Americans and immigrants, cost $12 (approximately $400 today). Steerage passengers typically slept in communal rooms with limited bedding and ate much less lavishly.

A first-class menu from one of the Clyde lines’ Jacksonville ships illustrates the experience of voyaging on one of these ships. The menu, typical of Victorian-era lavishness, includes delicacies of the time, such as celery or consommé royale, a meat broth served with cubes of custard floating on top. Both of these foods were indicators of wealth, as celery (at the time) cost more than caviar and up to a pound of meat was used to cook every bowl of consommé. Dinner was served at 6:00pm daily on the boats, and steerage-class passengers ate in a separate dining area. While we do not have extensive documentation of the treatment of steerage passengers coming to Fernandina, reports of Mallory shipwrecks sinking throughout the late 19th century tell the same story time and again—60 to 85% of the reported casualties in these accidents were from the steerage classes, indicating a higher value placed on the lives of first-class passengers by the company. Evidence of poorer peoples’ experiences are historically less likely to be documented and survive, so it can be difficult for historians to get a clear answers. Because of Fernandina’s turn-of-the-century status as Florida’s first resort town, connected to the flourishing shipping port of Jacksonville, surviving accounts of steamship voyages here are either from those wealthy enough to afford a vacation or from cargo companies.

Mallory steamship line office in Fernandina. Local agents of the Mallory line were Chas Davies and R.W. Southwick.

Mallory steamship line office in Fernandina. Local agents of the Mallory line were Chas Davies and R.W. Southwick.

The wealth and new arrivals that came to Fernandina via steamship helped spur the Golden Age of Fernandina, transforming the local economy and building the foundation of the modern tourism industry. Passengers included out-of-state residents getting their first taste of Florida via Fernandina, as well as also Floridians arriving from elsewhere in the state. The Mallory line advertised that interested Floridians could use the Florida Central and Peninsular Railroad—an 1893 descendant of David Yulee’s railroad from Fernandina to Cedar Key— to reach “the largest, most beautiful and deepest harbor on the coast of Florida”, before departing on their steamships. The above image from the 1880’s shows the local employees who ran the Mallory Steamship office in town. The undeveloped land behind the office gives the viewer a sense of how rural Fernandina was at the dawn of its Golden Age, although that rurality did not dissuade cosmopolitan travelers from using Fernandina’s port—local rail lines connected Fernandina’s depot (nicknamed “Steamers Wharf”) with Bay Street in downtown Jacksonville.

The halcyon days of steamships faded as the Golden Age of Fernandina came to an end. By the turn of the 20th century, the dedicated Mallory steamship docks in Fernandina’s harbor were used as loading docks for railroad crossties and lumber. The use of steamships to Amelia Island slowed with the expansion of Florida’s railroads. In 1893, rail connections were established between Jacksonville and another major Southeastern port, Savannah, and interest in Fernandina as a resort town waned with the establishment of Flagler’s railroad to new vacation destinations, such as Palm Beach and Miami. By 1940, only two round-trip voyages to Jacksonville on Mallory ships occurred, and the following year, the Clyde-Mallory docks in Jacksonville burned. By the end of the decade, the Clyde and Mallory lines were no longer in operation.

While ships in the Port of Fernandina today are much more likely to be diesel-powered, the rise of steamships illustrates a crucial moment in our town’s history. At a time of local transformation, steamships connected urban America and wealthy society with a developing Fernandina, enabling the small port town to find its niche as Florida’s first resort town and gateway to the rest of the state. It is easy to understand the excitement of visitors, watching from the deck of a steamship as the rural Victorian town crested the horizon. In the words of one such visitor, “there are few pleasanter winter resorts—or summer either—than this, with the beautiful Strathmore Hotel and beach in sight.”

_____________________________

References

Bob Bass, When Steamboats Reigned in Florida (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2008), 6-8.

Rick Kilby, Florida’s Healing Waters: Gilded Age Mineral Springs, Seaside Resorts, and Health Spas (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2020); Anya Grahn, “Tuberculosis Sanitariums: Reminders of the White Plague”, National Trust for Historic Places, https://savingplaces.org/stories/tuberculosis-sanitariums-reminders-of-the-white-plaque.

Staff of Mandarin Museum, “Harriet Beecher Stowe”, Mandarin Museum & Historical Society, https://www.mandarinmuseum.org/mandarin-history/harriet-beecher-stowe.

Bass, When Steamboats Reigned in Florida, 4.

Brandon D. Cross, “Mallory Steamship Lines”, Historic Marker Database, https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=224173.

United States Investor and Promoter of American Enterprises, vol. 3, (New York: Investor Publishing Company, 1893), 6.

Gray Edenfield, Amelia Island: Birthplace of the Modern Shrimping Industry (Gloucestershire, England: Fonthill Media)

Letter from Chas Davis, Agent, Mallory Steamship Lines, AIMH Collections, https://ameliaisland.pastperfectonline.com/archive/BD6C21D5-0603-4F25-8471-390850440945.

Metro Jacksonville, “The Steamships of Jacksonville”, https://www.metrojacksonville.com/mobile/article/2009-oct-the-steamships-of-jacksonville.

Steamboat, City of Jacksonville Christmas dinner menu, 1926. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory, https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/148700.; New York Public Library, “What’s on the Menu: Dishes, Celery”, https://menus.nypl.org/dishes/15.

“The City of Waco. Burned To the Water’s Edge.” The Inter Ocean (Chicago), Nov 10, 1875, 1. Accessed at https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-inter-ocean-robert-tarkintor-1823-1/39810614/; “13 BURNED AT SEA; A Fatal Fire on Board the Mallory Line Steamship Leona Off the Delaware Capes. TEN OF THEM WERE STEERAGE PASSENGERS. The Flames Spread so Rapidly That Little Could Be Done to Save Their Lives.” The New York Times, May 10, 1897. Accessed at https://www.nytimes.com/1897/05/10/archives/13-burned-at-sea-a-fatal-fire-on-board-the-mallory-line-steamship.html.

Mallory’s Ad, AIMH Collections, https://ameliaisland.pastperfectonline.com/photo/69317C38-8378-4C04-8CF0-935204340624.

Stereoview: C. H. Mallory & Co. Steamship Line Office, AIMH Collections, https://ameliaisland.pastperfectonline.com/photo/6586DE0F-9932-4DEB-B5C5-146724887671

Letter from Chas Davis.

Hill’s Crossties and Lumber Docks, AIMH Collections, https://ameliaisland.pastperfectonline.com/photo/A79BF832-877C-4677-AA66-070993330654.

Metro Jacksonville, “The Steamships of Jacksonville”.

United States Investor and Promoter, 6.