A Piratical Vessel

August 22, 2022by Jonathan M. Bryant

On June 28, 1820, Captain John Jackson of the United States Revenue Marine made a fateful decision. For several days he had heard stories of a “piratical vessel” anchored off Spanish St. Augustine, Florida. The ship carried not just hundreds of captives from Africa destined for enslavement, but the pirates had also kidnapped the son of the Governor of Spanish Florida.

The captain of the pirate ship threatened to hang young Cornelio Coppinger unless Governor Coppinger supplied his ship with water and food. The Governor refused, and a standoff ensued for several days. In response to this intelligence Captain Jackson took his command, the schooner Dallas, down the St. Marys River toward the sea.

The Dallas was a topsail schooner, officially an armed Revenue Marine cutter, the equivalent today of a Coast Guard cutter. Captain Jackson had a duty to suppress piracy and prevent the introduction of new captives from Africa. The piratical vessel was said to be large, and armed. Thus, before entering the Atlantic, Jackson anchored his schooner off the north point of Amelia Island and sailed the ship’s boat to Fernandina to request reinforcements. He was not requesting Spanish help.

While still officially part of Spanish Florida, since December of 1817 Fernandina had been occupied by American troops. Sent by the Monroe Administration to suppress the activities of the pirate Luis Aurey, the soldiers had continued to occupy Fernandina and Amelia Island since. This was a clear sign of the United States intention to take East Florida by any means necessary, as they had taken West Florida in 1810.

Captain John Jackson, however, needed soldiers to help him take on a large pirate ship. By the afternoon of June 28, Jackson returned to his ship with a dozen armed U.S. infantrymen. Then, riding the outgoing tide, the Dallas crossed the bar and went in search of pirates.

Around 7:00 a.m. on the morning of June 29, Jackson’s crew spotted sails to the southeast. Winds were light, but with as much canvas as the schooner could bear, the Dallas closed with the other ship. About 2:00 p.m., just offshore of Amelia Island, the Dallas was about two miles from the other ship. At that distance Captain Jackson could make out the details of a brig sailing northwest, a brig that resembled the reported pirate ship.

Jackson’s men hoisted the Revenue Marine flag, and the strange brig immediately turned to the northeast and threw out ever more sail, trying to escape. Topgallant sails, staysails, even studding sails appeared, all to catch as much of the light breeze as possible. But the sleek hull and schooner rig of the Dallas proved faster. By 3:00 p.m. the Dallas had closed to just a hundred yards off the starboard quarter of the brig, a ship five times bigger than the Dallas.

Suddenly, the brig cleared for battle, the crew loading and crouching down behind their cannon, taking down the light wind sails and backing the topsail to provide a steady gunnery platform.

The Dallas prepared its single cannon, and the dozen soldiers lined the rail, muskets at the ready. The Revenue Cutter continued to overtake the brig, sailing alongside “half a pistol shot” apart. The standoff lasted several minutes until it became clear that the crew of the strange brig were unwilling to fire. Captain Jackson then hailed the brig, demanding its identity.

“This is the Patriot brig of war General Ramirez,” came the reply.

Captain Jackson demanded the brig heave to and sent a boarding party. What they found Jackson had already guessed from the stench; there were hundreds of chained captives aboard. The commander of the brig, who gave his name as John Smith, was taken aboard the Dallas.

There he showed Jackson a document in Spanish that Smith claimed was a privateering commission from the Banda Oriental. The Banda Oriental was a beleaguered revolutionary state in South America at war with both Spain and Portugal. Smith then claimed to be lost and searching for the St. Johns River in order to find water for his ship.

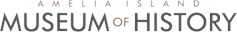

Illustration of captives onboard a slave ship.

Jackson didn’t buy the story. He felt sure this was the pirate who had kidnapped the son of the Florida Governor, threatened peaceful ships off of St. Augustine, and was now trying to illegally smuggle slaves into the United States. From members of the captured ship’s crew, Captain Jackson learned that the ship’s true name was the Antelope, and that it had been captured off the coast of west Africa by the purported privateers.

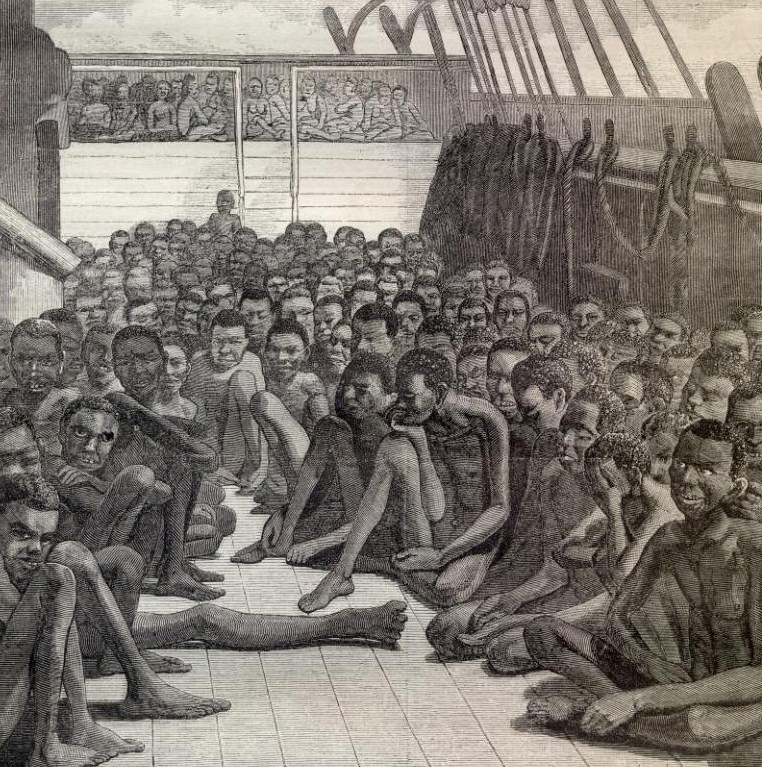

Meanwhile, Jackson’s boarding party reported that there were “two hundred and eighty-one African Negroes and the bodies of two others who were dead lying on the deck.” If sold as slaves at an average value, the captives would be worth more than one hundred thousand dollars, or close to three million dollars in 2022. If this value was compared to the size of the U.S. economy in 1820, then one hundred thousand dollars was equivalent to tens of millions of dollars.

Stowage onboard an Antelope-sized ship.

Captain Jackson had the entire crew of the Antelope brought aboard the Revenue Cutter as prisoners suspected of piracy. The boarding party now became a prize crew, with orders to take the Antelope into the St. Marys River and anchor there. The light summer winds made for slow going, and not until July 1, 1820, was the Antelope able to finally anchor near the town of St. Marys.

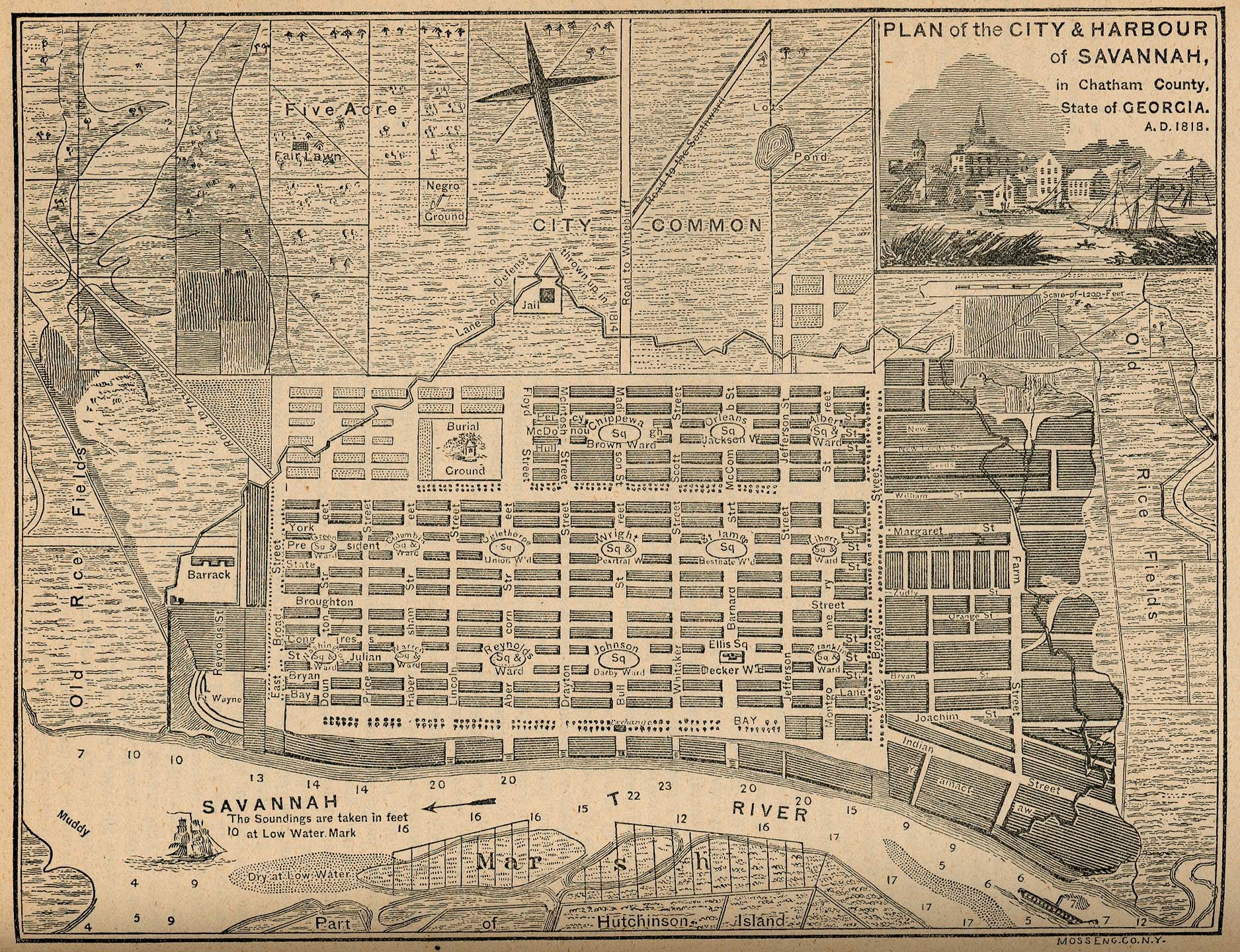

Jackson then took the Dallas and his prisoners to Savannah, where the news of the Antelope’s capture electrified the town. Savannah was in the midst of hard times, having suffered commercially from the Panic of 1819, a devastating fire in January of 1820, and would soon be virtually depopulated by a Yellow Fever epidemic. The arrival of so many valuable enslaved people seemed an economic Godsend to Savannah’s white elite.

Map of Savannah, 1818.

After reporting his capture of the Antelope, handing his prisoners over to the U. S. Marshal, and filing a claim in Admiralty Court the value of the captives, Captain Jackson sailed the Dallas back to Cumberland Sound where he found that six more captives had died and thirteen had simply vanished. Jackson suspected his First Officer, who had been left in charge of the Antelope, had sold some of the captives at either St. Marys or Fernandina.

Jackson ordered the Antelope to Savannah, and escorted the ship there, where on July 24, 1820, 258 living captives were turned over to the U. S. Marshal. The Marshal reported that the captives were starved and sick. He estimated that the average age was less than fourteen, and that 41% of the captives were children between the ages of five and ten. The terror of captivity, sale at the coast, capture at sea by force of arms, the middle passage, starvation, thirst, and the grizzly deaths at sea of more than sixty fellow captives had been largely inflicted upon children.

There followed a dramatic legal struggle over the fate of these captives, who if enslaved were worth a fortune. Under Federal law the captives should be freed and returned to Africa. Under Admiralty law the captives should be turned over to their true owner, a wealthy slave dealer in Havana, Cuba, who would have to pay Captain Jackson and his crew for salvage. It took eight years of litigation, three trips to the United States Supreme Court, and finally Congressional legislation to determine the future of these captives.

In this struggle, Chief Justice John Marshall wrote his most important ruling upon slavery. The issue, Marshall argued, came down to a conflict between the human right to liberty, and the right of property. Given the next four decades of United States history, it is easy to guess which right prevailed.

Jonathan M. Bryant is Professor Emeritus of History at Georgia Southern University. His most recent book, Dark Places of the Earth: The Voyage of the Slave Ship Antelope, was a finalist for the 2016 Los Angeles Times Book Prize.