Cotton in Fernandina: Then and Now

July 15, 2019In this article we will explore the history of cotton in Fernandina and the ecological issues affecting cotton today.

Please note: the State of Florida maintains strict regulations to protect cotton from invasive pests such as the boll weevil. Furthermore, the state forbids the removal of wild cotton, which is registered as an endangered species. If you have cotton growing on your property, please visit the Florida Department of Agriculture’s website to learn what law requires to prevent boll weevil infestation.

When we think about historically-significant industries around Fernandina Beach, we often think of lumber, turpentine, and shrimping. However, Fernandina was once well-positioned for the export of cotton to Northeastern textile mills and foreign markets. Although most of Florida’s commercial cotton was grown in west Florida around Tallahassee, there were significant pockets of cotton production near Fernandina that used our port for shipping.

In contrast, Sea Island cotton (aka. Egyptian or Pima cotton) was a labor-intensive crop that was more difficult to grow, yet far more valuable due to its extra-long staple fibers which produced a higher quality fabric. Many of the plantations near Amelia Island were able to grow Sea Island cotton. Some of the more famous ones include the Kingsley Plantation at the mouth of the St. John’s River and the Stafford Plantation on Cumberland Island.

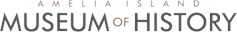

When the Union Navy seized the Sea Islands on the coast of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina, they also took control of some of the Confederacy’s most lucrative cotton plantations. In the words of one contemporary journalist:

“Nearly the whole of that most singular and important region of the South, in which Sea Island cotton is grown, is now in possession of the National forces; and this year there will be none of the exquisite fibre raised, unless it be cultivated by free-black labor. It is grown only on the sea-coast of the States of South Carolina, Georgia and Florida, and the line of its growth extends from John’s Island, just south of Charleston, to Amelia Island, Florida.” (The New York Times, April 3, 1862)

For this and other reasons, Amelia Island was a critical staging ground for efforts by the United States to confiscate Confederate stockpiles of cotton and to propagate future crops. The Union regularly shipped cotton out of the Port of Fernandina to textile manufacturers in the U.S. and Europe, which were hit hard by wartime cotton shortages.

Although many Confederates fled the coast to support the war effort, some local planters were willing to collaborate with the United States. During the occupation of Fernandina, Robert Stafford from Cumberland Island negotiated a deal with the military government so that he could continue to sell Sea Island cotton to mills in New York and Rhode Island. In return Stafford was permitted to keep his property without needing to sign an oath of allegiance to the United States.

Fernandina’s importance in the international cotton trade only grew after Reconstruction. On December 13, 1879, The Florida Mirror celebrated one of the most important cotton shipments in Fernandina’s history:

“The British steamship Kaieteur, sailed from this port Wednesday for Liverpool, taking a cargo consigned by Wm. Lawtey, valued at $60,975, the most valuable shipment ever made from this port. It consisted of 27,500 sacks of cotton seed (2,016,000 lbs.), 380 bags sea island cotton (146,240 lbs.), and 81 bags short cotton (38,278 lbs.).” (The Florida Mirror, December 13, 1879)

Despite decades of growth, the port of Fernandina eventually saw a decline after Henry Flagler broke ground on the Florida East Coast Railroad, which bypassed Fernandina altogether. Meanwhile, a new biological threat emerged to threaten cotton production across the United States.

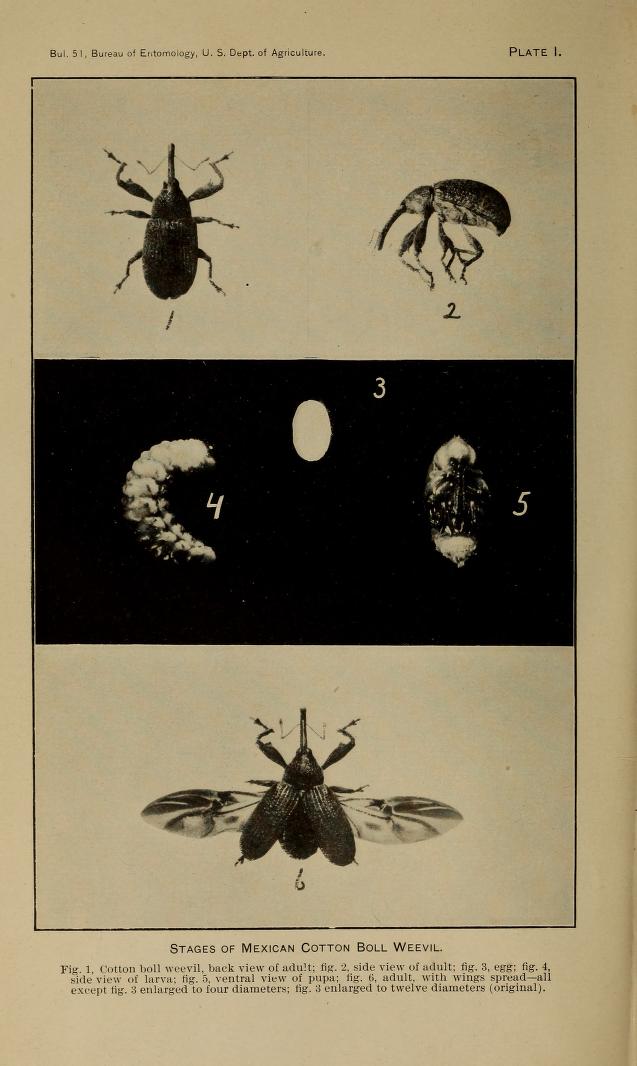

The boll weevil (Anthonomus grandis) came to the United States from Mexico in 1892, infesting all cotton-producing states from Atlantic to Pacific within a few decades. The invasive species crossed the Florida-Georgia line around 1917 and quickly spread across North Florida’s cotton plantations. Although Nassau County’s economy was not as heavily dependent on cotton as it was on other industries such as lumber, the farmers who grew cotton felt the impact of the weevil as it feasted on their crops.

Since the 1970’s the United States government has pursued a successful nation-wide program to eradicate the boll weevil from cotton-producing states. Due to careful cooperation between public and private interests, the boll weevil today is considered eradicated throughout most of the U.S.

To prevent the return of the boll weevil, the State of Florida strictly regulates the growth of cotton. Any person or organization wishing to grow cotton for noncommercial reasons must obtain a permit for a Homeowner or Demonstration Plot from the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

If you wish to see an example of Sea Island cotton, the Amelia Island Museum of History maintains a demonstration plot in our beautiful garden behind the museum. Here you will also find a selection of other plants that were used by residents of this area for a variety of purposes, including Indigo, coontie, and Yaupon Holly.