Anna Kingsley – A Life Like No Other

March 25, 2021Most of us have heard of Anna Kingsley through the Kingsley Plantation, south of Amelia Island on Fort George Island. But the life story of this amazing woman defies belief. Being born an African princess, becoming enslaved, emerging a free black woman and landowner, surviving two wars, and winning in the Florida judicial system as a woman of color in the 1840s are just the highlights of her story!

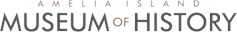

Anta Majigeen Ndiaye was born in what is now Linguère, Senegal in 1793. Her father was the ruler of the Kingdom of Jolof and her mother the daughter of an adjacent ruler, making her a princess. But at the age of thirteen she was captured, most likely by a neighboring tribe, and sold in the coastal town of Rufisque (now part of Dakar). Tribes in the area, who all had used conflict captives as slaves in their agricultural economies for centuries, found trading captives to Europeans for horses, guns, and gunpowder to be more lucrative.

Map of Senegal. Image from https://www.worldatlas.com/maps/senegal.

After surviving the Middle Passage, Anta was purchased by Zephaniah Kingsley at an auction in Havana, Cuba. Kingsley was a shipping merchant, dealing in enslaved people as well as other trade goods, and investing his profits in the Spanish Territory of Florida. Anta (now Anna) arrived, pregnant with Kingsley’s child, at Laurel Grove on the St. Johns River in 1806. She was the second black woman at Kingsley’s plantation to bear him a child.

Anna resided in the Kingsley main house and was given full supervision of the household and the enslaved families nearby. Anna excelled at her role, partly because it was not unlike her former life in Senegambia – her father had co-wives and her family had owned enslaved people as well. She was determined to fill the role of “first wife,” making life better for her children.

By 1811, Anna had three children and was running a retail store on the St. Johns River, selling goods Kingsley imported to planters up and down the river. Many thought she was a free black woman because of her competence, even though she was only eighteen. Zephaniah did free Anna and her three children that year, fearful they would be sold should he die at sea.

One must understand the difference between racial politics in territorial Florida versus the southern United States to understand a man like Zephaniah Kingsley. Spain recognized three castes of people – whites, free blacks, and slaves. Free blacks could intermarry, inherit property, own property, travel freely, and access the court system. Kingsley, a Quaker by birth, believed in manumission as well as the ability of enslaved people to purchase their freedom. The “task system” of slavery was common in Spanish Florida, wherein slaves were assigned tasks each day and, once completed (usually by midafternoon), they could work on their own gardens, create items for sale at Sunday markets, and otherwise save money to pay for their freedom. At his plantations, Kingsley often employed people he had previously enslaved for straight wages.

With her freedom, Anna moved to a five-acre homestead across the river from Laurel Grove. She continued to supervise Zephaniah’s household, run the retail store (which was moved across the river as well), run her own farm with slave labor, and raise her three children, a daunting workload.

After only one year of calm, chaos arrived. The Patriot War saw Zephaniah detained by rebels and the Laurel Grove home taken by marauders as a base of operations. Both free and enslaved blacks were in peril from Georgians running rampant across the territory. As a Spanish gunboat passed by, Anna took it upon herself to canoe out and detain them. She told them of the marauders, now hiding in the trees, ferried out over twenty free and enslaved blacks, and went back to set Laurel Grove afire, followed by her own farm buildings. For this bravery, Anna was awarded 350 acres of her own by the Spanish government.

Zephaniah returned shortly after to the remains of Laurel Grove, which he swore to rebuild, but also took advantage of an opportunity to acquire a plantation on Fort George Island that had belonged to John MacIntosh, one of the Patriot War ringleaders. All that was left there were the remains of the main house. Both plantations were rebuilt in the next two years. Anna spent those years in Fernandina, in a rented home in Old Town.

Kingsley spent most of those two years at sea, rebuilding his wealth and business, so Anna became the supervisor of construction at Fort George Island, traveling monthly to plan and check on things. Her hand can be seen throughout the grounds. No other plantation in America has slave quarters in a semicircle, as they are at Kingsley Plantation, and many think this was a nod to how buildings were known to be sited in Senegambian villages. The new homes for enslaved people were tabby, not wood, and had two rooms, a loft, a fireplace, and some space behind for family gatherings or gardens. Anna also had the “Ma’am Anna” house built, her home for 25 years. It had a large kitchen and parlor downstairs, with her bedrooms upstairs. She also bore her fourth child there.

Slave quarters at Kingsley Plantation arranged in a semicircle. Photo by Susan Martin.

The Adams-Onís Treaty made Florida a United States territory in 1821. Appointed to the East Florida Territorial Council in 1823 by President Madison, Zephaniah Kingsley argued for the continuation of racial norms in Florida and the protection of free blacks, but his efforts were in vain. Over the next six to eight years, most of those rights were rescinded or curtailed, including manumission.

Zephaniah Kingsley, always looking out for both his pocketbook and his family of black and mixed-race relatives, now found Florida less hospitable. He began deeding large swaths of property to his children of four different “wives” (other women he held enslaved), his plantation managers, most of mixed race, and others, although he kept enough for himself to remain extremely wealthy. By the mid 1830s, with conditions further deteriorating, he struck out in an amazing direction.

The Haitian Revolution in 1804 created a new black country independent of France. Kingsley had lived there for three years in his past and was familiar with the opportunities. He acquired 35,000 acres under his eldest son’s name, since white people were not allowed to own property there. He sold Kingsley Plantation to his nephew and in 1839 he moved his entire extended family, including Anna, and sixty enslaved people, to Haiti. Anna’s two daughters, who had married white men, remained in Duval County.

In 1842, with the Haitian property making money, Zephaniah divided all that property among his wives and children, with he and Anna’s oldest son, George, in charge. The condition placed was that any wife or child who left Haiti to return to the United States would permanently forfeit their share. He must have known he was dying, as he left Haiti once again, filed his will in Duval County Court, transferred more of his Florida properties, and sailed to New York, where he passed in 1843, at 78. His will left almost everything (over $5 million in today’s dollars) to his descendants in Haiti.

Kingsley’s sister immediately contested the will, saying all named heirs were still Kingsley slaves and that they had left for Haiti of their own free will (seemingly a contradiction). She also stated that under U.S. law, if they returned, they would be classified as “colored” and unable to inherit. George Kingsley took the lead to fight this, but headed first to New York City to get legal advice from his father’s lawyers. Unfortunately, while sailing back to Florida, his ship was lost at sea.

Anna was now left as head of everything. She departed for Florida, giving up her inheritance in Haiti, and took Martha Kingsley O’Neill to court. Actively engaged in her own case, her numerous contacts in the white community supported her and forced the courts to honor the 1821 Adams–Onís Treaty, which in fact guaranteed that all rights of free blacks under Spanish territorial rule would be continued under U.S. rule, a clause the U.S. had declined to enforce. Anna won her case by forcing the United States to live up to its promises.

Anna purchased a farm in the Arlington neighborhood in Jacksonville, between the properties of her two daughters. All three families still owned enslaved people. But in 1856, she sold that property and moved into a small house of her own on her daughter Martha’s land. She still had house slaves, cash, and income.

Anna and her two daughters’ families saw trouble on the horizon and sold most of their enslaved people by 1860. Both of her sons-in-law were Union sympathizers so in April 1862 they fled to Fernandina. Most of the family continued on to New York. Anna’s path is not known, but she likely went north as well.

Their return to Arlington in 1865 found all the family liquid assets gone. Each family sold land to get back on their feet. The Sammis family (John and Mary, Anna’s daughter) deeded many parcels in the Arlington area to their relatives along with any of their now freed slaves who returned, filling out the Arlington neighborhood. Anna died in May 1870, aged 77, at Martha’s home. Probate showed no assets and no debts for Anna, although interestingly her will stated that any enslaved people she owned would be sold and the proceeds divided among her children, a final comment on the complicated lives both she and Zephaniah lived.

Resources:

Schafer, Daniel L. Anna Madgigine Jai Kingsley: African Princess, Florida Slave, Plantation Owner. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2018.

Florida Memory: State Library and Archives of Florida. https://www.floridamemory.com/.

Main house at Kingsley Plantation. Photo by Susan Martin.